Last Updated on July 12, 2021

There has been a lot in the news lately about aducanumab (Aduhelm), a new monoclonal antibody treatment for Alzheimer’s disease.

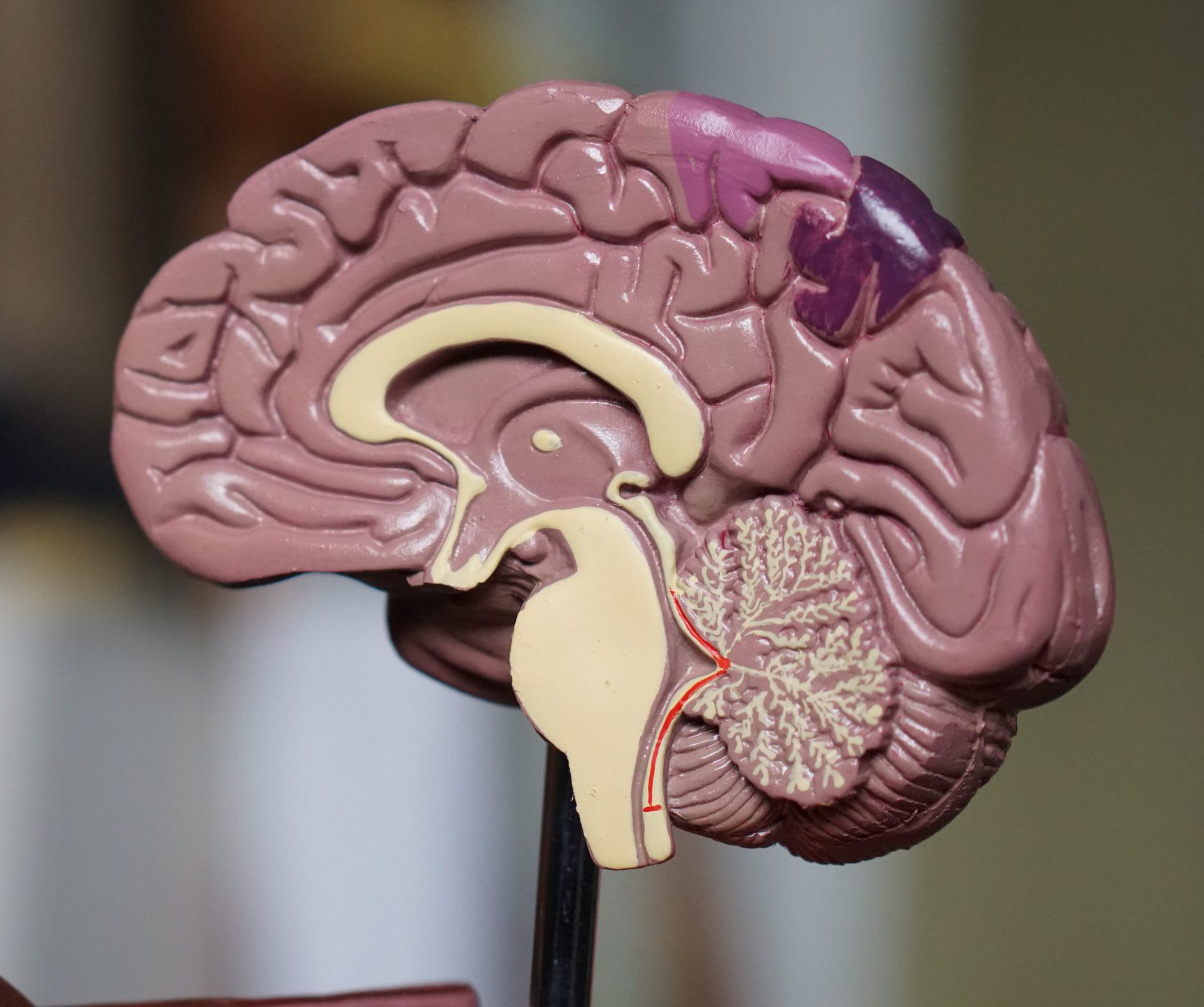

Alzheimer’s disease is a neurological disease and is the most common cause of dementia. It causes destructive, progressive, and irreversible changes in the brain. A common feature is the accumulation of a protein called amyloid-β in the form of plaques and tau tangles. Both are thought to cause cell death, but they have not yet been shown to be the cause of Alzheimer’s disease.

Aducanumab (Aduhelm), a drug that reduces amyloid-β plaques, was approved by the FDA on June 7, 2021 for treatment of all stages of Alzheimer’s disease. The approval was quite controversial for several reasons.

- Many experts are concerned that accelerated approval of aducanumab without convincing evidence is premature, especially since it was only tested on those with early Alzheimer’s disease but was approved for all stages. In fact, there is no evidence at all that aducanumab is effective in patients with advanced Alzheimer’s disease.

- The government is now looking at the issue since Alzheimer’s disease primarily occurs in seniors and Medicare will be picking up most of the tab for a medication that may have little benefit.

- The Boston Globe reported unofficial meetings between the manufacturer and an FDA director that may have influenced the decision.

The reason for the controversy can be confusing, so I will try and explain the different sides of the issue to help you understand what the fuss is about. There are basically three perspectives to consider when breaking down this issue.

- Those who believe there was not enough good evidence that aducanumab improves patients with Alzheimer’s disease to approve the drug, especially for use in those with advanced disease.

- Those who feel that the fact that there are no other available treatments justifies the use of aducanumab without convincing evidence and despite the known side-effects.

- Those who are concerned that the healthcare system cannot afford the $58,000 yearly cost of medication, along with the cost of brain-imaging tests, infusions, and provider visits, especially if the benefits are only subtle.

The Evidence

Basing medical treatments on solid evidence is of major importance to healthcare providers. There are too many examples of unhelpful or even harmful treatments that were not based on evidence but were continued through habit. Healthcare providers differ somewhat on what they consider to be good enough evidence to base medical decisions on, but most can agree that good evidence involves clinical outcomes. They also agree that a decision to use a new treatment can only be made if the effect on the patient outweighs the risk and the effect is significant/noticeable enough to be meaningful to the patient.

Clinical outcomes are patient oriented and look at benefits or risks experienced by people. This includes reduced mortality, resolution or control of an illness, improved symptoms or quality of life, or even lower cost. Many studies claim a significant benefit occurred when there is a statistically significant difference, which only means the difference was certain, but the difference had no meaningful (i.e. clinical) benefit for the patient.

Surrogate outcomes are those that only look at changes in diagnostic tests, medical imaging, or other biomarkers of disease. They do not take into account any effect on the patient’s symptoms. For example, does it really matter if treatment for your acid reflux reduces the acid in your stomach if there is no corresponding reduction in burning, pain, and reflux episodes, or is it worth taking statins to reduce your lipid levels if it is not also reducing your risk of stroke or heart attacks?

In other words, does it matter if the treatment improves the surrogate outcome without a corresponding improvement in the patient’s symptoms? For this reason, this is lower quality evidence of a treatment being effective.

- Although there are a few accepted exceptions, such as hemoglobin A1c to assess diabetes control, HIV testing to measure disease activity in the absence of symptoms, and tumor growth measured on a scan, the reduction in levels of amyloid plaques on PET scanning is not one of them.

- In fact, there is no solid evidence that amyloid-β build-up is directly responsible for Alzheimer’s disease or that reducing the amount of plaque seen on PET scans has any relationship to clinical improvement.

With this brief introduction to medical evidence, let’s look at the evidence for the effectiveness of aducanumab.

A 2016 trial with 53 patients having mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s Disease established the safety of doses 30 mg/kg or less.

The PRIME trial, which ended in July 2019, was the first to look at the effectiveness of aducanumab.

- It evaluated the effect of various doses of aducanumab over 12 months on 196 adults with prodromal or mild Alzheimer’s disease.

- Evaluations included the Clinical Dementia Rating-Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB), which is an integrated scale that measures both daily function and cognitive effects to gauge clinical changes. There were not enough patients to detect any significant clinical improvement.

- Patients were evaluated by positron emission tomography (PET) for brain amyloid-β pathology. Aducanumab reduced brain amyloid-β plaques over time, with more reduction at higher doses. The optimal dose was 10 mg/kg.

The ENGAGE trial enrolled 1,647 patients with early Alzheimer’s Disease who were treated up to 18 months with low dose aducanumab (3-6 mg/kg [higher dose for people with the APOE ε4 gene]), high dose aducanumab (6-10 mg/kg [same]), or placebo.

- The trial was terminated in August 2019 after showing no evidence of clinical benefit of either dose on numerous dementia rating scales, including the CDR-SB and Mini-Mental State Examination.

- However, PET scans did show reduced brain amyloid plaques.

The EMERGE trial enrolled 1,638 patients with early Alzheimer’s Disease who were treated up to 18 months with low dose aducanumab, high dose aducanumab, or placebo.

- The trial was terminated in August 2019 after showing no evidence of clinical benefit of either dose.

- However, PET scans did show reduced brain amyloid plaques.

- Patients from the EMERGE trial continued to be evaluated for 3 months after the trial was discontinued. It was noted that those in the high-dose group had begun to show some positive benefit during that time. Some experts felt the effects were not meaningful, being no greater than the changes seen in a given patient from week to week.

Without going into detail, there were other concerns about the trials other than the unexplained difference in outcomes between trials, such as how many sites were involved, the limited duration of the trial, the post hoc nature of the evidence, too many patients with incomplete follow-up, and many types of bias.

The Need

The disease burden from Alzheimer’s is huge, with more than 6 million patients in the United States alone. Since there are no previous treatments for the disease with any lasting benefit, the FDA considered it a priority to make something available even if it wasn’t ideal. The decision to approve aducanumab is based more on hope and need rather than rigorous scientific evidence.

Vigorous appeals for approval by patient advocacy groups, such as the Alzheimer’s Association, families, and those with Alzheimer’s disease also affected the decision.

The FDA balanced the risk of the drug, which appears to be low, with the potential benefits. Since there seemed to be some improvement in one of the aducanumab studies, the FDA decided, against the advice of their advisory committee, to put it on the market while the company conducts confirmatory trials to ensure that it works in case it can help some people in the meantime. The FDA gave the manufacturer nine years to do this.

The Cost

Aducanumab has the potential to be a gold mine for its manufacturer. Its hefty price plus the 6 million possible recipients in the United States alone will make it quite profitable. So who is going to pay for all of this?

- Since Alzheimer’s disease primarily occurs in seniors, the federal government will be picking up most of the tab through Medicare — some of which comes from income taxes.

- States will contribute since many patients with Alzheimer’s disease, including those on Medicare, are on Medicaid.

- The price tag could be enormous ($56,000 per year for 6,000,000 people over 9 years = $3 trillion for just the medication), which is more than the current $2.3 trillion federal deficit.

Another cost of treatment is the side-effects of the medication which include headache, brain swelling, bleeding, balance problems leading to falls, stomach issues including diarrhea, and disorientation. A comprehensive list of side effects can be found at drugs.com.

The Bottom Line

While it may seem straight-forward to evidence-based medicine advocates who argue that there is no firm proof it helps people yet, it is not for those who are desperate for anything that will have even the slightest impact on those with Alzheimer’s disease. It remains to be seen what that long-term impact will be, if the cost will be prohibitive over time, if the meetings between the manufacturer and the FDA had an impact on the decision, and the results with other promising medications being developed, some pending approval.

There may be some unintended consequences.

- Having an approved medication may affect ongoing research. Patients may opt for aducanumab over the new drug being studied, even if the new drug may work much better, to avoid the possibility of getting placebo.

- Continuing focus on the study of anti-amyloid-β drugs may delay the study of drugs targeting a different pathway that may be even more effective.

- If aducanumab is ultimately shown to be ineffective over the nine years the manufacturer has to complete post market and confirmatory studies, there will have been an enormous amount of money spent for no benefit. There may also be too many anecdotal reports of benefit to remove it from the market without a lot of protest.

In response to the controversy over the past month, the FDA updated their approval of aducanumab on July 8 emphasizing that the drug should only be used in patients with the earliest stages of disease — the group studied in the clinical trials.

The NeedyMeds Diagnosis Information Page for Alzheimer’s Disease has information on commonly prescribed medications, links to programs that may provide prescriptions at low or no cost, and other resources available for those affected by Alzheimer’s. For further assistance navigating available resources, call our toll-free helpline at 1-800-503-6897.